A true apology consists of a sincere acknowledgement of wrongdoing, a show of empathic remorse for why you wronged and the harm it caused and a promise of restitution by improving ones actions to make things right. Without the follow-through, saying sorry isn’t an apology, it’s a hollow ploy for forgiveness.

That’s the kind of “sorry” we’re getting from tech giants — an attempt to quell bad PR and placate the afflicted, often without the systemic change necessary to prevent repeated problems. Sometimes it’s delivered in a blog post. Sometimes it’s in an executive apology tour of media interviews. But rarely is it in the form of change to the underlying structures of a business that caused the issue.

Intractable revenue

Unfortunately, tech company business models often conflict with the way we wish they would act. We want more privacy, but they thrive on targeting and personalization data. We want control of our attention, but they subsist on stealing as much of it as possible with distraction while showing us ads. We want safe, ethically built devices that don’t spy on us, but they make their margins by manufacturing them wherever’s cheap with questionable standards of labor and oversight. We want groundbreaking technologies to be responsibly applied, but juicy government contracts and the allure of China’s enormous population compromise their morals. And we want to stick to what we need and what’s best for us, but they monetize our craving for the latest status symbol or content through planned obsolescence and locking us into their platforms.

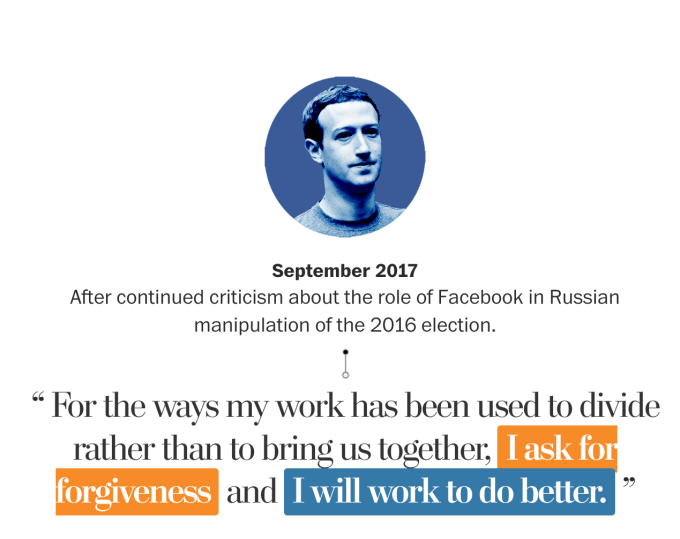

The result is that even if their leaders earnestly wanted to impart meaningful change to provide restitution for their wrongs, their hands are tied by entrenched business models and the short-term focus of the quarterly earnings cycle. They apologize and go right back to problematic behavior. The Washington Post recently chronicled a dozen times Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has apologized, yet the social network keeps experiencing fiasco after fiasco. Tech giants won’t improve enough on their own.

Addiction to utility

The threat of us abandoning ship should theoretically hold the captains in line. But tech giants have evolved into fundamental utilities that many have a hard time imagining living without. How would you connect with friends? Find what you needed? Get work done? Spend your time? What hardware or software would you cuddle up with in the moments you feel lonely? We live our lives through tech, have become addicted to its utility and fear the withdrawal.

If there were principled alternatives to switch to, perhaps we could hold the giants accountable. But the scalability, network effects and aggregation of supply by distributors has led to near monopolies in these core utilities. The second-place solution is often distant. What’s the next best social network that serves as an identity and login platform that isn’t owned by Facebook? The next best premium mobile and PC maker behind Apple? The next best mobile operating system for the developing world beyond Google’s Android? The next best e-commerce hub that’s not Amazon? The next best search engine? Photo feed? Web hosting service? Global chat app? Spreadsheet?

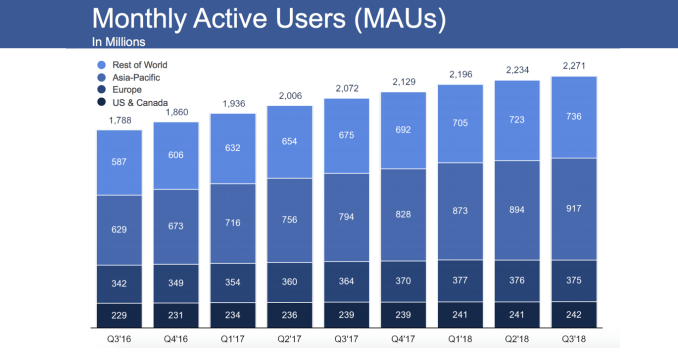

Facebook is still growing in the U.S. and Canada despite the backlash, proving that tech users aren’t voting with their feet. And if not for a calculation methodology change, it would have added 1 million users in Europe this quarter too.

One of the few tech backlashes that led to real flight was #DeleteUber. Workplace discrimination, shady business protocols, exploitative pricing and more combined to spur the movement to ditch the ride-hailing app. But what was different here is that U.S. Uber users did have a principled alternative to switch to without much hassle: Lyft. The result was that “Lyft benefitted tremendously from Uber’s troubles in 2018” eMarketer’s forecasting director Shelleen Shum told the USA Today in May. Uber missed eMarketer’s projections while Lyft exceeded them, narrowing the gap between the car services. And meanwhile, Uber’s CEO stepped down as it tried to overhaul its internal policies.

This is why we need regulation that promotes competition by preventing massive mergers and giving users the right to interoperable data portability so they can easily switch away from companies that treat them poorly

But in the absence of viable alternatives to the giants, leaving these mainstays is inconvenient. After all, they’re the ones that made us practically allergic to friction. Even after massive scandals, data breaches, toxic cultures and unfair practices, we largely stick with them to avoid the uncertainty of life without them. Even Facebook added 1 million monthly users in the U.S. and Canada last quarter despite seemingly every possible source of unrest. Tech users are not voting with their feet. We’ve proven we can harbor ill will toward the giants while begrudgingly buying and using their products. Our leverage to improve their behavior is vastly weakened by our loyalty.

Inadequate oversight

Regulators have failed to adequately step up either. This year’s congressional hearings about Facebook and social media often devolved into inane and uninformed questioning, like how does Facebook earn money if its doesn’t charge? “Senator, we run ads,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said with a smirk. Other times, politicians were so intent on scoring partisan points by grandstanding or advancing conspiracy theories about bias that they were unable to make any real progress. A recent survey commissioned by Axios found that “In the past year, there has been a 15-point spike in the number of people who fear the federal government won’t do enough to regulate big tech companies — with 55% now sharing this concern.”

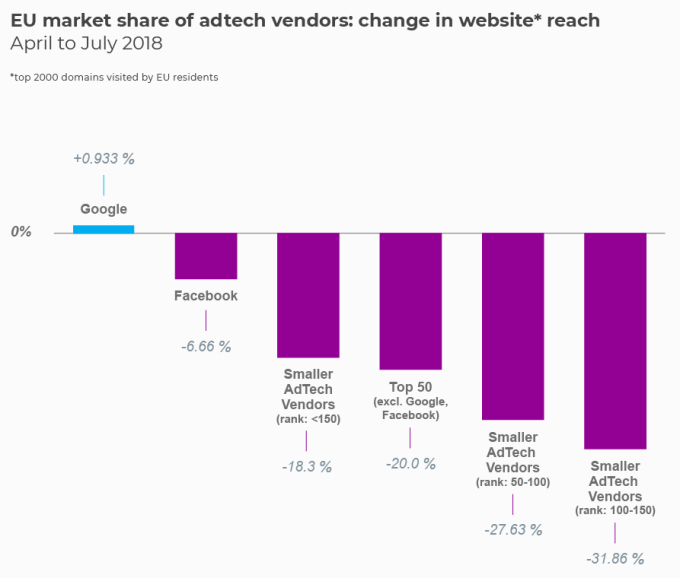

When regulators do step in, their attempts can backfire. GDPR was supposed to help tamp down on the dominance of Google and Facebook by limiting how they could collect user data and making them more transparent. But the high cost of compliance simply hindered smaller players or drove them out of the market while the giants had ample cash to spend on jumping through government hoops. Google actually gained ad tech market share and Facebook saw the littlest loss while smaller adtech firms lost 20 or 30 percent of their business.

Europe’s GDPR privacy regulations backfired, reinforcing Google and Facebook’s dominance. Chart via Ghostery, Cliqz and WhoTracksMe.

Even the Honest Ads act, which was designed to bring political campaign transparency to internet platforms following election interference in 2016, has yet to be passed, despite support from Facebook and Twitter. There’s hasn’t been meaningful discussion of blocking social networks from acquiring their competitors in the future, let alone actually breaking Instagram and WhatsApp off of Facebook. Governments like the U.K. that just forcibly seized documents related to Facebook’s machinations surrounding the Cambridge Analytica debacle provide some indication of willpower. But clumsy regulation could deepen the moats of the incumbents, and prevent disruptors from gaining a foothold. We can’t depend on regulators to sufficiently protect us from tech giants right now.

Our hope on the inside

The best bet for change will come from the rank and file of these monolithic companies. With the war for talent raging, rock-star employees able to have huge impact on products and compensation costs to keep them around rising, tech giants are vulnerable to the opinions of their own staff. It’s simply too expensive and disjointing to have to recruit new high-skilled workers to replace those who flee.

Google declined to renew a contract with the government after 4,000 employees petitioned and a few resigned over Project Maven’s artificial intelligence being used to target lethal drone strikes. Change can even flow across company lines. Many tech giants, including Facebook and Airbnb, have removed their forced arbitration rules for harassment disputes after Google did the same in response to 20,000 of its employees walking out in protest.

Thousands of Google employees protested the company’s handling of sexual harassment and misconduct allegations on November 1.

Facebook is desperately pushing an internal communications campaign to reassure staffers it’s improving in the wake of damning press reports from The New York Times and others. TechCrunch published an internal memo from Facebook’s outgoing VP of Communications Elliot Schrage, in which he took the blame for recent issues, encouraged employees to avoid finger-pointing, and COO Sheryl Sandberg tried to reassure employees that “I know this has been a distraction at a time when you’re all working hard to close out the year — and I am sorry.” These internal apologies could come with much more contrition and real change than those paraded for the public.

And so after years of us relying on these tech workers to build the product we use every day, we must now rely that will save us from them. It’s a weighty responsibility to move their talents where the impact is positive, or commit to standing up against the business imperatives of their employers. We as the public and media must in turn celebrate when they do what’s right for society, even when it reduces value for shareholders. If apps abuse us or unduly rob us of our attention, we need to stay off of them.

And we must accept that shaping the future for the collective good may be inconvenient for the individual. There’s an opportunity here not just to complain or wish, but to build a social movement that holds tech giants accountable for delivering the change they’ve promised over and over.

For more on this topic:

from Social – TechCrunch https://ift.tt/2DWTFlg

No comments:

Post a Comment